Battery storage deployments, both with and without solar, have been in a new growth phase that has smashed quarterly records consistently while costs have continued to fall. Nonetheless, the maturity of the industry is not always reflected in the information available to financial decision makers, writes renewable energy lawyer Adam Walters from Stoel Rives LLP.

This is an extract of an article which appeared in Vol.27 of PV Tech Power, Solar Media’s quarterly technical journal for the downstream solar industry. Every edition includes ‘Storage & Smart Power,’ a dedicated section contributed by the team at Energy-Storage.news.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Complex technology, complicated markets

Seasoned renewable energy lawyer Adam Walters from Stoel Rives argues that procurement in the battery storage space is currently like a sort of Wild West. Here, Walters describes to Energy-Storage.news editor Andy Colthorpe some of the finance risks that face this maturing industry around procurement issues.

Ensuring supply chain robustness, ensuring customers understand the warranties and performance claims they are getting from manufacturers as well as navigating the patchwork nature of market opportunities are among the significant challenges he sees in the market today, particularly in the US.

“I got into utility-scale solar back in 2008, when it was just kicking off in the US. And then I moved on to Asia and kicked it off in Australia a few years after that. What you saw with PV, of course, is how rapidly it came down the cost curve for CapEx and ultimately became commoditised. You had the big shake up in around 2011 in solar PV, with the Chinese coming in with incentives for their manufacturing industry and essentially blowing out of the water, the European and American manufacturers.

There were very few survivors of that. We’re not seeing that in battery storage, but what we are seeing is the rapid decline down the cost curve that is very similar to solar. It hasn’t been quite as exponential as solar has so far, for battery storage. It certainly came down like that, and then it’s somewhat flattened out over the last two or three years. Perhaps that’s because you don’t have the same glut of supply as was seen in PV in 2011, 2012.

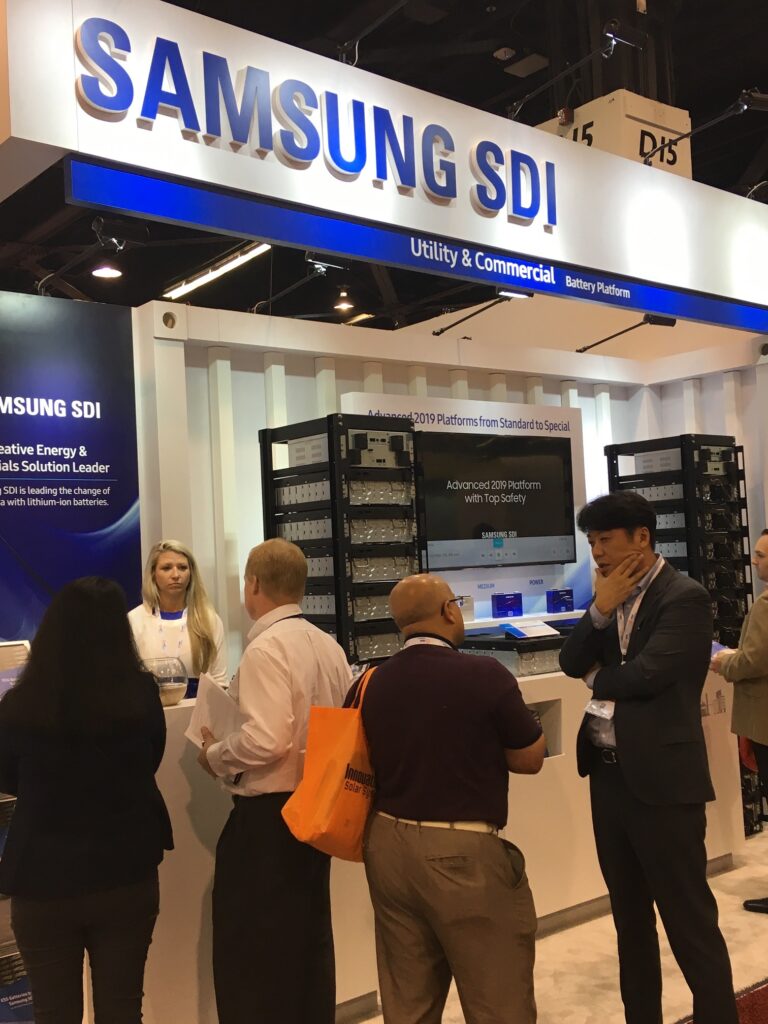

The other big difference is where the players started out. You really saw in batteries, the Koreans, Samsung SDI and LG Chem, being the early leaders along with Panasonic to a lesser extent. So Asia was already a leader for batteries. Once we started to see the stationary storage industry take off, the Chinese didn’t catch up quite as quickly.

Tesla’s kind of a whole different animal altogether in being an auto manufacturer that designs its own cells and jumped into that space along with Panasonic. In the last two years, you’re starting to see the Chinese manufacturers really start to take over, but I just don’t expect to see that kind of dominance that we saw with PV.

We are going to see a more balanced market where you have different players in different parts of the world, with Europeans and North Americans still being competitive. And part of that is the technology is different. I don’t think battery systems are going to get commoditised as easily as solar panels.

A lot of it is in the energy management system, or the battery controller, where you’re talking about firmware, operating battery systems and optimising for market conditions, power purchase agreement (PPA), temperature, climatic conditions, and all of that. It’s a more complex bit of technology than solar PV was, so I think we’re not going to see prices crash as quickly and we’re also not going to see one country completely dominate.”

Batteries for life, or for the lifetime of the batteries

“You have something that does something very simple. It stores energy, it sits idle, and then it discharges energy, that’s all it does, just those three things. But it’s how, and when, those three things occur that determine the value of the battery system. The other real key thing and key difference between this and PV is that availability is a critical part of the value of a battery system.

Whereas with solar PV, once you’ve got the PV system commissioned and operating, it’s going to sit out there and just generate electricity more or less for 20 years, and up to 35 years. Of course, you have to change out the inverters and other components eventually, but it’s just going to keep doing that.

Whereas a battery system, you have more complexity in the hardware and the use case and how the battery is used

is going to determine the life of the battery and when components need to be replaced. So availability is just a much more critical part of the ownership and operation of a battery than it is a solar system where you might have availability guarantees, but it’s not a high risk, it’s not something you worry terribly about and it’s also not something that you’re going to get heavily ‘dinged’ on in your PPA. Because those are mostly energy-only contracts.

There’s a difficulty in financing standalone energy storage projects right now in a lot of markets, because you may not have a long-term off-take contract, or a 20-year power purchase agreement, for instance.

In some countries, or markets, you might have a robust enough ancillary services market where you can model it based upon capacity that’s online and maybe get financiers comfortable with the revenues that you’re going to be able to generate from that, in addition to revenues from energy arbitrage. But unless you can find somebody that’s going to give you a long-term capacity contract for standalone storage, right now that’s the real difficulty — how do you finance it?

A lot of our clients are independent power producers (IPPs), and they’re doing solar-plus-storage. There you have an easier case, because for the most part they’re choosing DC-coupled battery systems and so really what they’re just doing is maximising the energy uptake from the combined system. So you don’t have the financing issues as much.

There’s a lot of financeability issues with the product offerings, though. What I emphasise for my clients who are looking to procure battery systems or energy storage systems, is that you’re not focus- ing on the engineering, procurement, construction (EPC) partner nearly as much.

You’re focusing much more on the technology, on the long-term service contracts, the availability guarantees, the energy retention guarantees that you’re getting from the battery integrator or OEM. You have to make sure that you’re going to have somebody standing behind that battery system, in the long-term for the lifespan of the battery, which in most cases is going to be 15 years without battery augmentation. You have to emphasise those warranties and guarantees, and long-term service contracts.”

Augmenting: The reality

“My main point when I’m advising clients, is to think through these issues upfront and when you’re initially putting out your RFP to tender to determine exactly what you want, and what you think your financing parties are going to require.

Augmentation is another big point. You usually have a standard availability guarantee that’s long-term and then an optional battery augmentation contract, which is really CapEx. What financiers are used to seeing is basically, ‘Well, this is a power plant that’s going to operate for X number of years at X power capacity’. They’re less used to this idea, that you’re going to have a bunch of CapEx already in year six or year seven, or the energy capacity is substantially degraded by that point.

So there’s different ways to do it. You can do it as an upfront CapEx contract, I’ve seen some suppliers do it that way. Or you do it through the long-term service agreement (LTSA) as part of that contract, and then that’s built into the annual maintenance fee.

A lot of it just depends on who the end user is, and what their preference is. Do they want to try to finance 100% of the CapEx of an augmented battery upfront? Or do they want to try to do it as OpEx over the course of 20 years? Or do they want to just take a punt on it and decide to just take the standard OEM energy retention guarantee and see what the revenue situation and use case of the battery looks like and five years down the road decide whether to engage someone to augment the battery. You’re going to pay more to do it that way down the road in some cases, because the original system hasn’t been designed for that, but we’re seeing different ways, and all of those ways can be successful.”

It’s like the Wild West out there

“The battery storage procurement space is still a kind of Wild West and I don’t see it becoming any less chaotic just yet. However there are some things that are starting to coalesce, in terms of standard offerings. Round trip efficiency is a good example.

Nowadays, it’s pretty rare to see a battery contract that doesn’t have round trip efficiency guarantees that run usually the same duration as the energy retention warranty. So they’re going to warrant round trip efficiency over 10 years or, typically sometimes 15 years, just like they warrant energy retention. So we’re seeing that whereas, just maybe three years ago, you didn’t. So there are some kinds of things that are starting to become more standardised.”

Adam Walters is a transactional, commercial and project lawyer specialising in offering legal counsel to clients across a range of industries including wind, solar PV, telecoms, manufacturing, water and of course, energy storage. Having spent 10 years as an in-house lawyer for solar and storage industry heavyweights First Solar, Tesla and SolarCity, he now practises in the energy development group at independent law firm Stoel Rives.

This is an extract of an article from Volume 27 of PV Tech Power, our quarterly journal. You can buy individual issues digitally or in print, as well as subscribe to get every volume as soon as it comes out. PV Tech Power subscriptions are also included in some packages for our new PV Tech Premium service.