The US energy storage industry remained “remarkably resilient” during what most of us have found to be a difficult year – to say the least. Energy-Storage.news editor Andy Colthorpe speaks with Key Capture Energy’s CEO Jeff Bishop and FlexGen’s COO Alan Grosse – two companies that made 2020 one of growth in their energy storage businesses – to hear what lessons can be learned and why economics rule.

For so many reasons, 2020 will be a year that is remembered for a long time, but not remembered with fondness. It will be difficult to forget the pandemic which has taken so much from us all and whichever side of the political fence you are on – or even if you take no side at all – the world seems a very divided place. And that’s before we even start thinking about the climate crisis.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

For the US energy storage industry, still the world’s leader in adopting batteries for the grid and for renewables, it has however been a year in which clear steps forward have been taken. Research firm Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables found that in the third quarter of 2020, 467MW / 764MWh of energy storage was deployed around the US across all market segments. This was more than double what was recorded in the previous highest deployment quarter and Wood Mackenzie head of energy storage analysis Dan Finn-Foley described the industry as having been “remarkably resilient” to the impacts from coronavirus lockdowns.

All this, despite reported supply chain slowdowns earlier in the year, permitting delays due to officials staying at home and the difficulties of getting onto sites and customers’ properties. In an interview for Energy-Storage.news in late November,

US national Energy Storage Association (ESA) CEO Kelly Speakes-Backman said that 2021 will be an “important year for energy storage” and that the industry will continue to grow at an accelerated rate – with at least 3.6GW of storage expected to come online.

The prospect of working with the incoming Biden-Harris administration, which included climate protection and environmental concerns prominently in campaigning during the election is also a welcome one, Speakes-Backman said. Meanwhile, a lot of progress happens at state level, and the ESA CEO pointed out in her interview that Arizona, Maryland, Nevada and Virginia were among states to step forward and show leadership on energy storage policy, along with the more commonly talked-about likes of California and Hawaii.

Speaking for this article with Jeff Bishop, CEO at developer Key Capture Energy (KCE) and Alan Grosse, chief operating officer (COO) at installation services and technology provider FlexGen – two contrasting companies that have managed to make 2020 a pretty good year, energy storagewise – we hear how they approach the industry and its variety of business models; which regional markets in the US work best and why; which technologies and partner companies they rely on to get the job done and the future of energy storage both as an enabler of renewable energy and a cleaner grid and as a competitive alternative to existing grid infrastructure options.

Expecting everything to be in flux

Jeff Bishop, Key Capture Energy’s CEO says that 2020’s been a year of “expecting everything to be in flux,” which for someone involved in an industry as nascent and disruptive as energy storage is perhaps a more familiar feeling than it would be for many others. Yet KCE’s plan to get more than 1GW of projects in operation by the end of 2023 remains on track, Bishop says, and 2021 “will be an exciting year”.

“We knew going into this industry that storage was going to be really hard. Each project presents a unique mix of technical, commercial, regulatory, and development in ways that didn’t exist with wind or solar as those industries were emerging and taking off,” Bishop says.

The way KCE has made energy storage project development stack up, is by looking at the energy landscape and trying to “figure out what the grid needs in five to 10 years from now,” Bishop says.

“There are opportunities that allow for certain technologies over others and we approach energy as if we were a thermal independent power producer (IPP). So: if you were a natural gas company 10 years ago, what are the fundamentals you would need and what are the core competencies that you need in a company?”

The answer, Bishop says, is strong project development teams, engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) teams or partners, market development staff that watch what’s going on day-to-day, combined with commercial structuring that allows KCE to recover its capital expenditure (CapEx) to put back into growing the pipeline of projects still to come.

“That’s how we approached the industry. Because we do not have tax equity, we do not need the same structures that a wind or solar company would need, or the 20-year contracts. Instead, we’re able to go out into the market, get, let’s say, four to 10 year off-take contracts that cover a debt service, so that we can put project debt on these projects and then be able to construct projects that are above our cost capital.”

Typically, KCE will go into states and regional transmission organisation (RTO) territories of the US where the company figures and expects there will be a market in two to five years’ time, but isn’t one yet today.

“We start small, and do 10 or 20 megawatt projects initially to figure out all the known unknowns within a given market. And then once we get comfortable with the revenues, with the market structure, with the regulatory environment, commercial structures, then we expand and go bigger into the 50 to 200 megawatts-sized projects.”

Opportunities driven by competitive advantages

Flexgen’s path into the grid-scale utility energy storage market has been a very different one, COO Alan Grosse says, if only because the company actually began doing microgrids, including several projects for the US military. The opportunity for batteries really came onto FlexGen’s horizon with equipment cost reductions from around 2014 onwards. Before that, battery storage’s cost was “prohibitively high,” Grosse says, and the majority of FlexGen’s projects were megawatt-scale microgrids using ultracapacitors that “only had enough storage for about 30 seconds worth of full power deployment”.

But FlexGen also made its way into Texas from 2018, focusing on the one-hour duration battery storage systems that make economic sense trading energy and grid services in the state’s Electricity Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) market. The “lion’s share” – or indeed the Li-ion’s share – of what the company has delivered this year as a technology and project services provider have been one-hour batteries in Texas and elsewhere.

“The perspective is one in which, wherever the market provides an opportunity, that’s obviously where you want to play. And so we are seeing a number of these ancillary services markets in Texas, in particular,” Grosse says, along with energy arbitrage and trading, to a lesser extent. FlexGen’s next year or so is also expected to be busy – Alan Grosse says that the company “will probably buy a little over 1.1GWh of energy storage for delivery between now and the first half of 2022”. FlexGen has done some international projects but focuses mainly on the US.

“Within the US market, which is obviously the one in which we play the most, our biggest markets in order of where we see quoting activity, where we’re building systems and where we see the market opportunity, are Texas, California, and then the northeastern US, so Massachusetts, to some degree and some of the independent system operator (ISO) zones in New York. Those are the areas that we see and then if I had to take a fifth, I would say of all places: Indiana.”

Grosse mentions Indiana, he says, because of the phaseout of coal. FlexGen is not an avowedly climate agenda-driven company with a mission, but Grosse says the economics of renewables-plus-storage are a “slam dunk” while states, utilities – and hopefully eventually the Federal government once more – are decarbonising and adopting clean energy policies and goals.

While the coal shutdowns also mean that more natural gas could be expected to come online in many places, FlexGen’s COO argues that a recently completed project the company did in Indiana epitomises how energy storage can be paired even with natural gas to provide efficiency and reliability increases and ultimately, a transitional pathway to decarbonisation.

FlexGen added 12MW / 5.4MWh of lithium-ion batteries to a natural gas plant for a utility in Indiana that can black start the turbines. Previously, this was done exclusively with diesel engines which are dirtier, noisier and less reliable, requiring frequent maintenance and incurring fuel costs. That customer is doing a Request for Proposals (RFP) for multiple gigawatts of solar, and has a number of coal plants in the process of closing down.

“Our black start project is colocated at an 800MW coal plant. They’re closing that coal plant down and they put the battery in to make their gas turbines more reliable because they’re in the process of building out a massive, massive footprint of solar and battery – solar-plus-storage.”

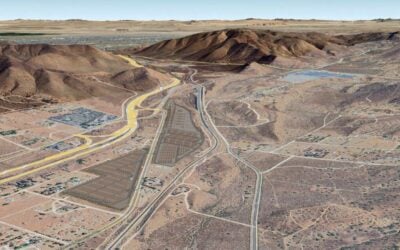

Cover Image: One of several FlexGen projects the company has delivered, stabilising power supply to communities around Houston, Texas. Each is around 10MW / 11MWh.

Energy-Storage.news’ publisher Solar Media is hosting the 2021 edition of the annual Energy Storage Summit in a new, exciting format from 23-24 February and 2-3 March, 2021. See the website for more details.

This is the opening extract of an article which appears in full in the latest edition of our quarterly technical journal, PV Tech Power (Vol.25), in ‘Storage & Smart Power’, the dedicated section contributed by the team at Energy-Storage.news. To download the entire article as an individual paper, or to subscribe to or download the entire 89-page book, visit the PV Tech Store.