Federal and local authorities alike consider the Imperial Valley, in the southern California desert close to the Mexican border, as having the potential to become the hub of a “world-class lithium industry”, even dubbing it ‘Lithium Valley’.

With the US lithium battery industry today almost entirely dependent on imports and almost all of those coming via China, it has become a strategic aim of the Biden Administration to reduce at least some of that dependency and capture more of the economic value at home.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

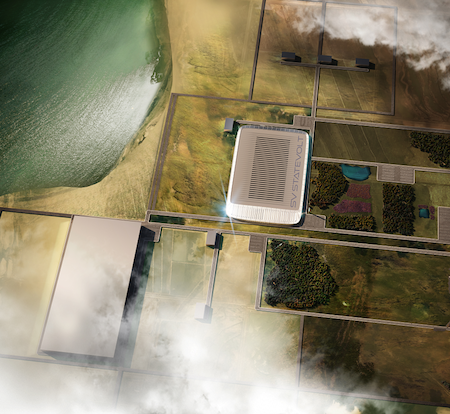

Imperial Valley is home to the shallow, extremely saline Salton Sea, an inland body of water accidentally created a few decades ago by the breach of a canal. Bordered by Riverside and Imperial Counties, the region is troubled, to say the least: one of California’s poorest regions, with both water and local air reported to be highly polluted, as this fascinating 2021 article from The Guardian explains.

Yet it is also home to significant geothermal energy resources and lithium-rich brine found there holds the key to why it has become a hope for the energy transition. Large-scale quantities of lithium could be extracted as a run-off from geothermal facilities, which could also be a low carbon power source for the whole process. In turn, that hope has also become hope for the rejuvenation of the area and its economy.

California’s energy policy and planning agency, the California Energy Commission (CEC), held a symposium in February 2020 on how the region’s fate could be turned around to host that “world-class lithium industry,” with the geothermal brine offering a “unique opportunity,” the CEC said.

Shortly after that, Energy-Storage.news reported on plans by Controlled Thermal Resources (CTR), a developer of geothermal plants looking to create a pilot plant at its Salton Sea Hell’s Kitchen project, aiming to scale up to annual production of 34,700 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) by 2025.

Master plan underway, 54GWh battery gigafactory plan announced

Last week, the Imperial County Executive Office sent Energy-Storage.news notification that the local authority is proceeding with its Lithium Valley Master Planning efforts, hoping to encourage lithium and other mineral recovery facilities development using the significant geothermal resource.

As well as expanding the availability of geothermal energy generation from new and existing facilities, the local authorities want to support “other renewable resource operations,” which could include clean hydrogen production, repurposing of organic materials and perhaps inevitably, lithium battery manufacturing in the area.

The county is preparing to contract for a resource plan — prepping Lithium Valley with environmental assessments and infrastructure planning options.

“This is a win-win approach that focuses on working with the public and industry by streamlining the development process while fully addressing the economic, environmental, and social needs of our community in an equitable manner,” Jesus Escobar, chairman of the Imperial County board said in a statement.

The latest news is that a 54GWh lithium battery gigafactory could indeed be on the way. Statevolt, a startup, has signed a letter of intent (LOI) with CTR which aims to use the Hell’s Kitchen Lithium and Power development to provide energy and feedstock for the US$4 billion factory.

“The development of lithium-ion batteries is crucial for the US to meet its goals to transition to net zero,” Statevolt founder Lars Carlstrom said.

“Today, we face a significant shortage in the amount of lithium that is required to meet the demand for electric vehicles. We are pioneering a new, hyper-local business model, which prioritises sustainability and resilience in the supply chain to solve this issue.”

Will it work?

Imperial County’s board applauded the Statevolt-CTR LOI announced yesterday, describing the plan as potentially providing a “much-needed economic boost” to the residents of the historically disadvantaged and underserved region. Some 2,500 jobs would be created by the manufacturing plant.

County chair Jesus Escobar called it a “major milestone for our region,” and “another step towards fulfilling the potential of Lithium Valley for a better and brighter Imperial County”.

Last week, Energy-Storage.news spoke to a number of stakeholders and experts in the battery energy storage market about Joe Biden’s invocation of the Defense Production Act, 1950s-era Cold War legislation, which enables the federal government to directly support manufacturing and the critical minerals supply chains in the US.

Several commentators reflected that the move is a positive one in terms of intent, but remains vague as to the nature of that support. Perhaps more importantly, it was pointed out that upstream operations such as materials extraction require investments and time. On the latter point, the permitting process alone can add several years to development timelines.

One of those commentators, US battery cell manufacturer KORE Power’s CEO Lindsay Gorrill, says of the Lithium Valley plan that the Salton Sea project could put “enough lithium there that lasts for years,” tapping into California’s abundant reserves of the natural resource.

“But again, it’s a permitting issue. It’s an environmental issue. It’s long term. The government really has to look at it in this way. They have to look at the whole picture, and if you want to go down this track — which we all do — you have to support the upstream, and you have to support it quickly,” Gorrill says, adding that the demand-supply gap will only become greater and create an even bigger problem.

Another, Caspar Rawles, from lithium battery supply chain information provider Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, agrees that permitting is the biggest stumbling block and barrier to entry to the minerals extraction business, not just in the US, but almost everywhere in the world.

On the Salton Sea, he says the form of Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) proposed has only been done at a small scale commercially so far. The majority of expansions Benchmark has seen in development will be hard rock mining of spodumene in Australia, or solar evaporation of brine ponds in South America.

Commercialising DLE “could accelerate things” for the supply chain and this could be key to the success of the industry and its role in the energy transition, Rawles says. However, and this is a big however, DLE is more complicated than the name might imply. It may also not be possible to replicate Lithium Valley’s way of doing things elsewhere, hence the “unique opportunity” the CEC referred to.

“The important thing with DLE is the technology hasn’t been cracked commercially. What makes it more complicated is that a DLE process that works on one brine is almost certainly not going to work on another,” he says.

“That’s because of the raw materials and the impurity profile of the brine. What is in that brine with the lithium really has an impact on your process, and you need to develop a separate process for every brine effectively. What that means is that even if one person gets it right at one project it doesn’t unlock the rest of them. Each one needs to go through the same process.”

Nonetheless, if it can be “cracked,” DLE can be a much quicker, and more sustainable, method than digging new mines and pumping brine up to massive evaporation ponds at high altitude salt flats in Chile or Argentina.

At those facilities, it takes about two years to enrich brine to the point it can go through a chemical refinery and be converted to lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide.

“Obviously, that’s a big time window. Two years, even by the time you start pumping [up brine], you then have to wait two years before you can get any product. DLE would mean that you just take the brine from the ground, pump it in real time, and you get the lithium extracted in that way. So that would be a key kind of change, should that become widely successful.”

Construction began at the CTR pilot plant in November 2021, adding 50MW of geothermal energy generation capacity by late 2023 and an estimated 20,000 tonnes of lithium hydroxide production in 2024.