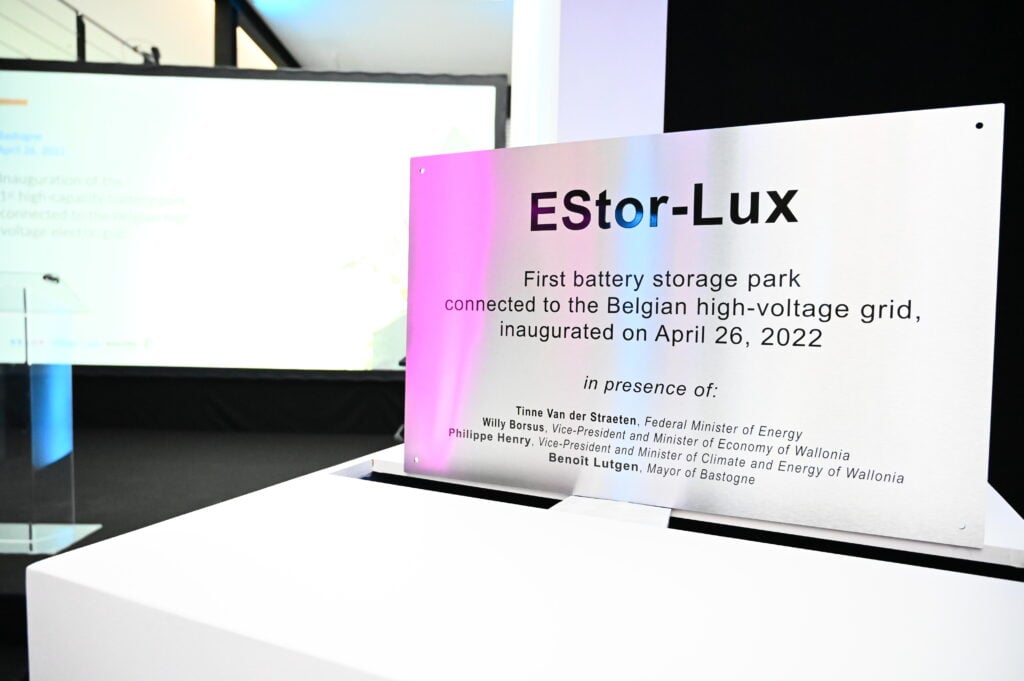

In April, an inauguration was held for the 10MW/20MWh EStor-Lux battery storage project in Bastogne, Belgium, with attendees including the country’s federal energy minister Tinne Van der Straeten.

The lithium-ion battery energy storage system (BESS) was among the first projects to go online using Fluence’s Gridstack modular BESS solution and has been working to provide flexibility to Belgium’s grid since the end of 2021 through optimiser Centrica Business Solutions.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

More than 30GWh of balancing capacity had been provided between switch-on and the inauguration event and as things stand, EStor-Lux is the country’s biggest BESS to date.

As was always likely to be the case, even bigger projects are now on the way, with two separate 25MW/100MWh projects from Trafigura joint venture (JV) Nala Renewables and a Nippon Koei JV financially closed and in construction.

However, EStor-Lux will always have the accolade of being a pioneering project, say Pierre Bayart and Cedric Legros, co-managing directors of BSTOR, the company behind it.

BSTOR is a brand-new company formed by the merging of Bayart and Legros’ former outfits: Rent-a-port Green Energy, which Bayart came from, is a clean energy development subsidiary of marine and industrial development group Rent-a-port. Legros joined from SRIW, an investment and economic development vehicle from the Belgian region of Wallonia, where the EStor-Lux project is located.

Although the company name and the BESS mark new territories, the project has its origins as far back as the late 1990s European wind boom and there is plenty more still to come, the pair say.

BSTOR owns 75% of the ESTOR-Lux project’s equity, with backing from what Bayart calls “fully traditional project investors who know each other from having investments together in the offshore wind business in Belgium”.

Pierre, you said that when you began this project in 2018, at 10MW and 20MWh it was considered “huge”. Of course, today other projects are coming along that are bigger, but Estor-Lux is online and can be considered something of a milestone project. What does it tell us about Belgium – and perhaps Europe’s – battery storage industry today?

Pierre Bayart: For us, we still see two kinds of project developments in Belgium. Since 2016, the TSO (Elia Transmission Belgium) is not even buying ancillary services with contracts longer than one year and even at one year, it’s not sufficient to build up a bankable business model.

What we’ve seen is two types of project development: one is more balance sheet-based, people buying an asset and taking the risk. An approach that we have brought forward, which is maybe more similar to the UK industry, is project finance-backed development.

This has been part of our ambition as of Day One, to source significant, fully non-recourse project finance on this project. Maybe an even bigger achievement than the size of the project is that 50% of the project was financed by fully non-recourse project finance, senior debt.

And this is where we draw the advantages for merchant development. We could solve the value of the project on a fully merchant basis based on corporate contracts, a bit similar to power purchase agreements (PPAs) for renewable energies, but what we call the flexibility purchase agreement in our case.

With there being so many bubbles in the energy sector crashing because of inappropriate policy-driven developments, this is the type of contract we believe in. We believe that this is the key to unleashing developments that will not depend on any political decision that can take ages to be taken.

We are of the opinion that developments should follow the needs in the markets more than the other way around because we know that there’s going to be tremendous need for storage in the system, for the system.

Attracting project finance for merchant developments has proven tricky in some markets. One example of that is Australia, where batteries have been shown to make good revenues, but it’s quite difficult to actually model what those revenues will be and the returns over the long-term. What sort of modelling, or expectations, were you able to give investors for ESTOR-Lux?

PB: [On this project] it’s a blend of private investment companies owned by public shareholders or fully private investment companies. Fully traditional project investors who know each other from having investments together in the offshore wind business in Belgium.

Basically, how we got all our sponsors but also the lender on board, is much more through investing huge efforts in trying to understand the main drivers of the markets we were targeting, much more than very complex ‘Monte Carlo’ black box simulations.

There has been some forecasting, but really the reason why our lenders and our sponsors follow is because we could give them comfort on the fundamentals of the market, of the flexibility market that we’re about to derive our revenues from and understanding that our revenue assumptions were just totally realistic or even conservative in the uncertain long run.

Cedric Legros: Even more than the revenue forecast, you need to convince the sponsors and the lender that the market positioning is a smart one – that’s a really key point. You’re starting from the basics, you’re making the risk matrix and basically, you need to reach the most optimal risk allocation between the different stakeholders.

You’ve hinted that the origins link back to work done years ago as part of the offshore wind industry. Can you tell us a little more about that and why you’ve determined not only this project but also that this industry is the right one for BSTOR and its partners?

PB: The true genesis of this project is almost in the late 1990s. Our companies have invested together in the very early years of offshore wind development, when everyone was saying that going to construct wind turbines 30 kilometres from the shore with 40-metre depth was either crazy or stupid, or both!

In the end, we delivered pioneering projects and then also a large share of the volumes of offshore wind development in Belgium. But in Belgium we only have 60 kilometres of shoreline, so we knew that wouldn’t be an endless story… we had to find a diversification option to keep the show going.

Secondly, we realised Belgium is a small and integrated electric system and that integrating all this offshore wind would require flexibility.

We started around 2014-15 to look into storage, mainly heavy infrastructure projects like pumped hydro, or energy atolls on the sea. It all started from there already with the partners who are in the project now. We looked at greenfield and brownfield pumped hydro and then in the meantime, battery technology emerged as something viable and bankable.

At a certain moment, we made the switch to just go for battery standalone in about late 2018, or the beginning of 2019. It took us a couple of years to close the financing, one more year to close the project and now we’re up and running. The site selection for the project in Bastogne was also a gamechanger.

CL: There was already [heavy] industry based at the site with significant access to the grid – connection capacity to the grid. It takes time to get grid connection capacity from a greenfield perspective and it costs a lot as well.

Basically, having this kind of redundancy allows us to rent this connection capacity, so it allows us first to reduce the cost and secondly to speed up the development and construction of the project.

PB: The main challenge for the moment in Belgium is lead time to get access to the grid.

Actually, one of the reasons why we abandoned the PHES developments is that it was economically viable, but you would have lead times of five to seven years before first revenues from your investment decision.

With batteries you can solve it because you can reduce this to 12, 18 or 24 months, depending on the context. But as far as getting access to the grid you would need four years, so we had to find a workaround. This was the perfect place because we could access the existing substation without having to go for a greenfield connection to the high voltage network.

I’ve heard from Giga Storage, a battery storage company in the Netherlands, that it’s extremely difficult to get a grid connection, even for housing developments or new commercial premises. Is it a similar sort of situation in Belgium?

CL: It’s not worse than the Netherlands as Belgium is not as populated as the Netherlands per square metre, but we’re going to end up there. It is going to be one of the biggest challenges for the whole energy transition: how to push all the needs for generation, new electrification and new flexibility on the existing infrastructure because building new transmission lines takes about 15 years. That’s going to be a huge challenge for us and for all the people involved in energy both as producers and as consumers.

Another thing that’s interesting about ESTOR-Lux is that while other markets kicked off with a lot of shorter duration projects, you guys have gone immediately for two hours. What was behind that decision and when did that come about?

PB: We could have invested in short duration projects as early as 2015, 2017. But then you can only do frequency containment, and for us this is like being paid for not doing anything, it’s just to stay on standby in case there would be a big frequency deviation that occurs every 10 years.

Bankability in the context of no subsidies and no long-term contracts meant being able to deliver energy.

We want to use the BESS as much as possible, because we believe that we should balance the grid before it ends up into frequency deviations, because those are where the volumes are where you can sell energy not only to the TSO but also to market players.

Obviously, you’re not looking for subsidy or policy-driven projects. But it’s clear that Belgium’s energy minister, Tinne Van der Straeten, did support this project by coming along to the inauguration. How do you view that support from above?

PB: We deliver projects for the moment that add flexibility. In the long run, energy storage will also need to actually supply peak power with stored renewables. For this activity, you might need some subsidies, but for us, at our stage of development, it is more important to fight for equal rights for accessing the grids and accessing the market than for subsidies.

On the other hand, there is an adequacy problem in Belgium, and it is the task of the Minister to make sure that there is sufficient capacity. So, it’s also normal that she calls upon projects like us, even if they’ve not asked for subsidies, to deliver the capacity when it be needed.

For us, there is no conflict between the two positions, it’s just different use cases, and different challenges and also different responsibilities.

The federal government has done a tremendous job from the beginning by anticipating the clean energy package, to grant us such kind of equal rights in the access to the grids as early as 2017. This made our projects possible. Also, our TSO has made a tremendous jump and efforts in opening all the markets to all technologies, including storage. So, we’ve been supported by policy where we have needed to be, not in terms of subsidies, but in terms of those equal rights.

What comes next for BSTOR? More projects in Belgium? Expanding elsewhere?

CL: First of all, we are focusing on Belgium. Surrounding countries as well, but Belgium first, and we have a pipeline around 150MW in development. We are working quite hard in order to bring the next project to financial close.