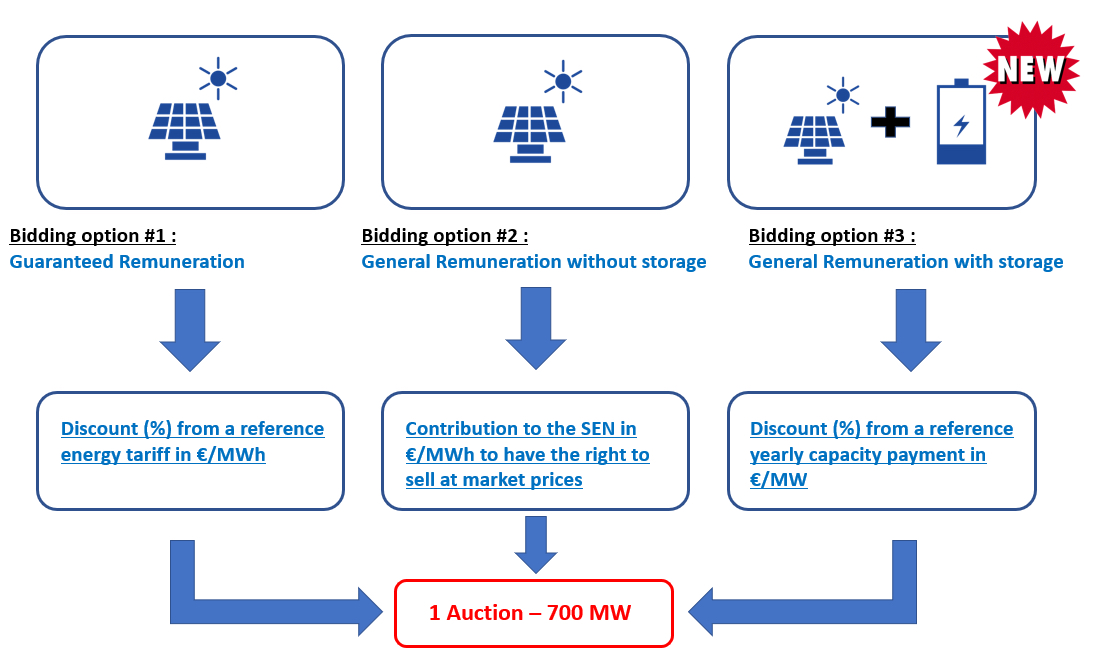

Capacity payments that solar-plus-storage developers could earn from winning in Portugal’s big 700MW solar tender are an interesting step, but will likely only be a supplementary income to add to what could be earned from ancillary services, Energy-Storage.news has heard.

“I would say that it’s an interesting first step, because actually we do see from our perspective a lot of developers who are interested,” Tanguy Poirot, market analyst with Clean Horizon told Energy-Storage.news.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

However, for the business case for battery storage to stack up in the West European country, a 15-year contract for capacity will have to be bolstered by participation in ancillary services markets. Poirot and his colleague, Clean Horizon’s head of research Corentin Baschet, explained in a recent interview how the storage option works in the auction, which is taking place now having been postponed from Springtime due to COVID-19.

“The auction revenues for capacity is not likely to be enough to have a competitive storage system, with standalone solar plants, so we expect revenues to be accumulated from other sources,” Tanguy Poirot said.

Essentially, to prevent the system from paying out big due to price spikes caused by volatility in the wholesale market, payments to solar-plus-storage developers will be capped off. So while this presents a good start, there are revenues that can be accessed for supplying frequency regulation in both Portugal and neighbouring Spain – if regulatory design can fall in line with the speed with which technology is advancing.

Regulatory mechanisms that are not yet favourable to storage

Primary frequency control is “not really accessible,” Poirot said, because it is mandatory for thermal generation units in the Iberian Peninsula to provide this ancillary service. Individual storage developers could in theory do “some sort of one-to-one contract with potential thermal generator developers,” Poirot said, but in practise this is not really happening in the region.

“On the other hand you have the next type of reserve, secondary reserve, which is basically the same in Portugal and in Spain, regulated by a market mechanism but not really favourable to storage. As is often the case in many countries there is this kind of regulatory void so the participation of storage is unclear.”

Revenues for secondary reserve in Portugal can however reach up to €160,000 (US$182,500) per MW/year, if assets can fully participate, but current clearance participation rules prevent energy storage from doing so continuously, due to state of charge management issues. So the best available option may be for storage developers to participate in that secondary reserve market “from time to time,” complementing their capacity payment revenues.

European ‘harmonisation’ of secondary reserve offers promise for future

However, the goalposts are expected to shift in the near future. At the policy level the European Union’s parliamentarians appear to be onboard with idea of energy storage playing a prominent role in the continent’s future path towards net zero by 2050, things are also, perhaps more pertinently, expected to change quite quickly on the regulatory and technical level.

The secondary reserve services is going to get “harmonised” across much of Europe, with a common European project, Platform for the International Coordination of Automated Frequency Restoration and Stable System Operation (PICASSO).

“The principle is to share this secondary reserve energy from one country to another to lower the operating cost for transmission system operators (TSOs),” Poirot said.

“Given the scope of this project we expect a lot of participating countries including Portugal and Spain to adapt their secondary reserve and to standardise,” he continued, with the market design likely to be based on the German secondary reserve market.

That market is regulated by two types of selection: the first for reserve capacity, remunerated through capacity payments while the second “aims at selecting assets with the lowest cost of energy,” replacing an existing pro rata activation system in Portugal and Spain, which is “not good for storage in terms of state of charge management”.

“In the future, with the implementation of that PICASSO Project we’re going to secondary reserve get standardised across a lot of countries and we’re going to see a merit order activation for these assets and that could help storage to participate more efficiently.”

Corentine Baschet adds that in addition to Europe-wide “harmonisation” of ancillary services that will open the markets up to energy storage, the landscape of the primary reserve market in Portugal (and Spain) could also change dramatically in the coming years. With the auction-winning assets expected to begin commissioning in 2024, plenty could happen before and during the expected 15-year lifetime of those storage systems.

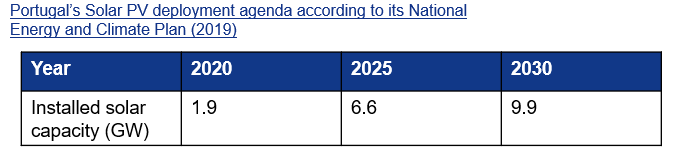

That earlier mentioned trading of primary reserve obligations held by thermal generators could become more viable, because as Baschet pointed out, “batteries are more competitive to provide primary reserve,” while in the bigger picture, Portugal’s National Energy and Climate Plan as filed to meet the terms of the European Union’s Clean Energy Package includes a target for 8GW of new solar PV by 2030 and a phaseout of coal.