National Grid has outlined how renewables could participate in the UK’s Capacity Market, unveiling technology-specific de-rating factors that range from 1–15%.

The Electricity System Operator announced its proposed methodologies at an industry consultation event held in London yesterday and attended by our UK sister site Current±, starting its work of establishing the finer details of how renewables could compete for capacity contracts in practice.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

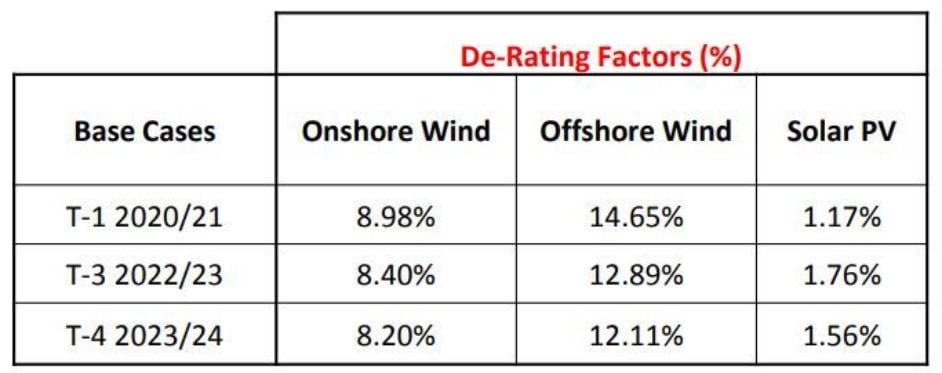

However renewables, and especially solar, stand to provide only a marginal contribution to how the energy system can respond to stress events if the ESO’s de-rating factors are anything to go by.

The indicative de-rating factor for solar for forthcoming delivery years ranges from 1.17% to 1.76%, representing how solar’s contribution to stress events, which predominantly occur outside of daylight hours, is negligible. Instead, solar’s contribution is almost strictly limited to enabling battery storage units to reserve their output until a stress event requires it.

Onshore and offshore wind meanwhile stand to have a more meaningful contribution with wind factors ranging from 8.2% to 14.6%. Battery storage technologies meanwhile will retain the de-rating factors applied to them last year.

The government Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) published a call for evidence on the prospect of renewables being eligible for Capacity Market contracts in August last year, but it is down to National Grid as the Electricity Market Reform delivery body to determine how it will work in practice.

Equivalent Firm Capacity

National Grid confirmed it had used Equivalent Firm Capacity (EFC) as a basis to determine de-rating factors, describing it as a “very useful construct to normalise the security of supply contribution of non-conventional adequacy resources” such as variable renewable generators.

It’s not the first time EFC has been used by National Grid. It is principally used to determine the contribution of wind power when producing its annual Winter Outlook document and was also used to determine the de-rating factors applied to short-duration battery storage technologies in the Capacity Market last year.

An EFC is defined as the precise amount of perfectly reliable firm capacity a resource can displace while maintaining the exact same level of risk on the system. Naturally, the more variable a generator is the less reliable firm capacity it maintains, and in relation to battery storage the shorter the duration of the battery the less reliable firm capacity it maintains.

However there remains debate over distinctions within EFC calculations, whether an incremental, average or combined EFC is taken across all technology types. National Grid has recommended that an incremental EFC is adopted, deciding that it makes more sense as the capacity value of renewables depends on the build-out rate (i.e. more significant quantities of wind and solar on the grid would seemingly increase system volatility at particular times).

The Capacity Market is currently suspended following a ruling from the European Court of Justice, with UK politicians and European Commission officers apparently working to resolve the ‘temporary’ situation, which has arisen as a result of clean energy technology provider Tempus Energy’s challenge to the decision to grant the CM with state aid approval.

Power curves

Technology power curves also play a central role in contributing towards the development of de-rating factors. National Grid uses NASA’s MERRA atmospheric dataset against site performance data to calculate the ‘long run average contribution’ of weather-dependent resources to determine how they can contribute to security of supply.

For wind technologies, this is made simpler by high levels of data and National Grid took the step of updating its notional power curves for both onshore and offshore wind, something it had not done since 2015 and 2016 respectively.

These updates, made using new data compiled and analysed from a number of operational wind farms in the UK, resulted in “meaningful updates” to their respective power curves.

Furthermore, given the differences in generation patterns and production between onshore and offshore wind, National Grid has elected to separate them into individual asset classes and apply different de-rating factors.

Solar however was complicated by a lack of available data given that the technology has only been deployed in meaningful scales since 2014. To determine the solar PV power curve, National Grid partnered with the University of Reading to develop a single power curve for all PV resources (domestic, C&I and utility-scale) using past solar PV power measurements provided by Sheffield Solar and NASA’s MERRA solar irradiance data set.

At the event yesterday, National Grid was questioned by the audience on the sense of producing a single power curve for all types of solar PV. Utility-scale PV plants, given the siting and technology advantages they have over most residential systems, stand to be significantly more productive per megawatt than residential systems and it was argued that they could be treated differently. National Grid replied by stating that it is wholly reliant on the data it has at its disposal and implored the solar industry to respond to the consultation with relevant datasets if possible.

Capacity assumptions and de-rating factors

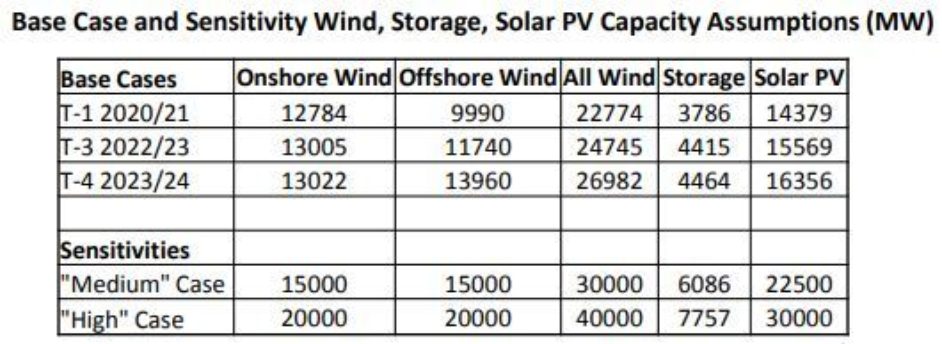

The final piece of the puzzle is National Grid’s capacity assumptions which are taken into consideration for its base cases in the T-1 2020/21, T-3 2022/23 and T-4 2023/2024 delivery years. The chart below indicates National Grid’s base cases for all renewables and storage technologies (storage’s figure includes a notional 2.7GW of long-duration pumped storage).

As a result, onshore wind’s de-rating factor for the delivery years ranges between 8.2–9%, offshore wind’s are between 12.1 and 14.6% and solar, given its notional contribution to grid supply when stress events are most likely to occur, has been handed de-rating factors of between 1–2%.

National Grid said solar’s EFC would have been “almost negligible” had it not been for the introduction of short-duration storage technologies. The thinking behind this is by contributing towards the country’s energy demand during daylight hours, solar can delay the introduction of battery storage output, providing a small but meaningful contribution towards meeting stress events.

There is, however, the potential for trends to change as renewables penetration on the grid continues to grow. While the incremental EFCs of renewables generally fall slightly with increasing penetrations – the more wind there is on the system, the less valuable wind is during a stress event – solar and storage were described as having a “mutually beneficial interaction” as their penetrations grow.

As a result, the System Operator said it remained open to altering the de-rating factors attached to these technologies as the system continued to evolve.

Next steps

The full list of methodologies, base cases, assumptions and recommendations have been published this morning on the EMR Delivery Body website, and National Grid is accepting responses to the de-facto consultation until the end of the month.

These will feed into a response to be published by National Grid by the end of February.

However National Grid’s Daniel Burke warned that there remains a long way to go before renewables can participate in CM auctions, not least because of the need for policy reform.

Any introduction of renewable energy into the CM would require regulatory overhaul from BEIS and market regulator Ofgem, matters which, Burke said, mean it is “quite feasible” to “take some time”.