India’s energy storage industry is at a turning point as developers, financiers, and policymakers work to define viable business models for the next wave of large-scale battery projects.

While the market remains young, aggressive pricing in recent tenders, new financing models, and growing opportunities in the commercial and industrial (C&I) sector are shaping the next phase of growth.

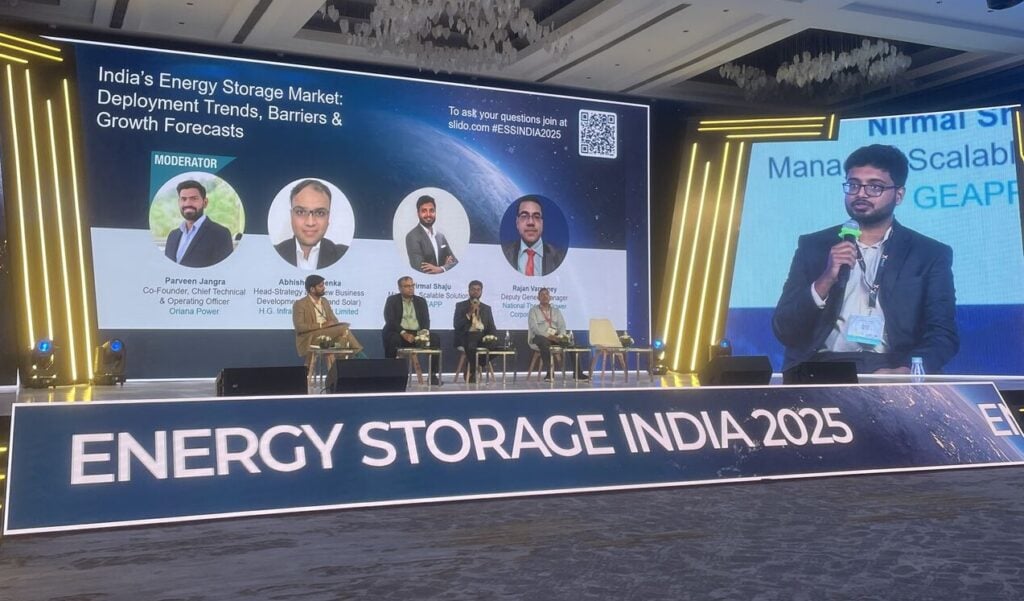

During the Energy Storage Summit India 2025 held in Greater Noida last week, a panel on India’s energy storage market deployment trends, barriers and growth forecasts brought together key industry voices to discuss the evolving dynamics of the sector.

The discussion, moderated by Parveen Jangra, chief technical and operating officer, Oriana Power, reflected the challenges and opportunities shaping India’s energy storage journey, from aggressive market pricing and evolving tenders to financing and second-life use of batteries.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

Price wars and market psychology

Speaking on market trends, Abhishek Goenka, head of strategy and new business development (BESS and Solar) at HG Infra Engineering, said developers are still trying to understand why “prices have become so aggressive in a very, very short term.” He added, “It is not like the market is dropping at ten percent every month, but the prices in the market are dropping at ten percent.”

According to Goenka, the rush to bid low is partly driven by fear of missing out. “There is a mixed fear among developers that if they do not have a foot in the door of battery storage, they may end up not getting qualified a few years from now, when the technical conditions of the tenders are going to evolve. Some developers could assume that they would have more than fifty percent residual life, and that could have a huge impact on the assumption of whether to go for aggressive pricing or be quite conservative.”

Technical factors were also highlighted. Rajan Varshney, deputy general manager, National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC), noted that while the “round-trip efficiency on the DC and AC side is eighty-eight percent,” this “does not take into account auxiliary power consumption.” Furthermore, he added, “At 85% efficiency, developers will have to buy additional power either through the state grid or the central grid.”

Meanwhile, Nirmal Shaju, manager, scalable solutions, energy-focused non-profit organisation (NPO) GEAPP, said that “It is a psychological market right now, not a rational one. People are bidding based on what others are doing, not on what makes commercial sense. The biggest challenge is the speed of price fluctuation. We are trying to build long-term models in a market that changes every three months.

The C&I frontier: How developers are creating business models

As the market evolves, attention is turning to the commercial and industrial (C&I) sector. “The C&I segment is quite an interesting space,” Shaju added.

“From a C&I perspective, they do not want to really spend a lot of upfront costs. We are seeing models emerging where developers lease batteries instead of selling them, to reduce the upfront cost barrier. If you can save net electricity billing at the end of the month, they are essentially going to replace the peak power time billing through this battery service.”

The structure resembles consumer financing. “Typically, when you are going to a C&I customer, it works like buying a car, there is a certain amount of upfront down payment, and then it is a leasing payment,” he explained. “That gives the customer a very limited amount of upfront cost, since all C&I products are site-specific.”

Developers are also acting as intermediaries. “Generally, the developer would be the one system acting with the C&I client, and the developer would be responsible to tie up with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs),” Goenka said.

“The way the developer would be de-risking themselves is through performance guarantees given by the OEMs, and the developer would pretty much act like a financier for the entire team.”

Sharing his thoughts on the existing business models, Varshney added, “Public-private models could help scale deployment because utilities bring the grid experience and the understanding of system operations, while developers bring commercial agility and innovative approaches. Together, they can ensure that projects are both technically viable and financially sustainable.”

BESS project financing

Goenka noted that financing is now a critical part of India’s energy storage development. As Indian lenders begin to assess risks, market players are also seeing greater support. “Due to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) temporarily coming down, there is a push from the government to support the best developers. Some nominal premiums over the banks’ marginal cost of funds-based lending rate (MCLR) are what you can anticipate, anywhere around eight to eight and a half percent with a good credit rating,” highlighted Goenka.

Developers with stronger financial profiles stand to benefit. “Anybody who is above investment grade should be able to get close to nine percent levels of investment,” Varshney added.

Goenka compared the asset life of battery projects to other long-term infrastructure. “If you look at the city gas distribution sector, you typically set up a line for a five-year period, but you end up operating it for twenty-five years,” he said. “In the packaged storage system, at the end of the earlier term, the requirement is not going to go away. Utilities and developers have to sit across the table and have a revised negotiation of what the residual life is and what kind of augmentation would be required.”

He also emphasised the relative security of battery assets. “Unlike solar, where there is uncertainty of generation, in the case of storage models you have an absolute number of revenue which you can ensure, and lenders are more comfortable with such kind of revenue models.”