For the US to succeed in creating a domestic energy storage manufacturing industry that can compete globally, it needs to look beyond today’s dominant lithium-ion technologies.

That was the view of directors from three Department of Energy National Laboratories that Energy-Storage.news spoke with recently.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

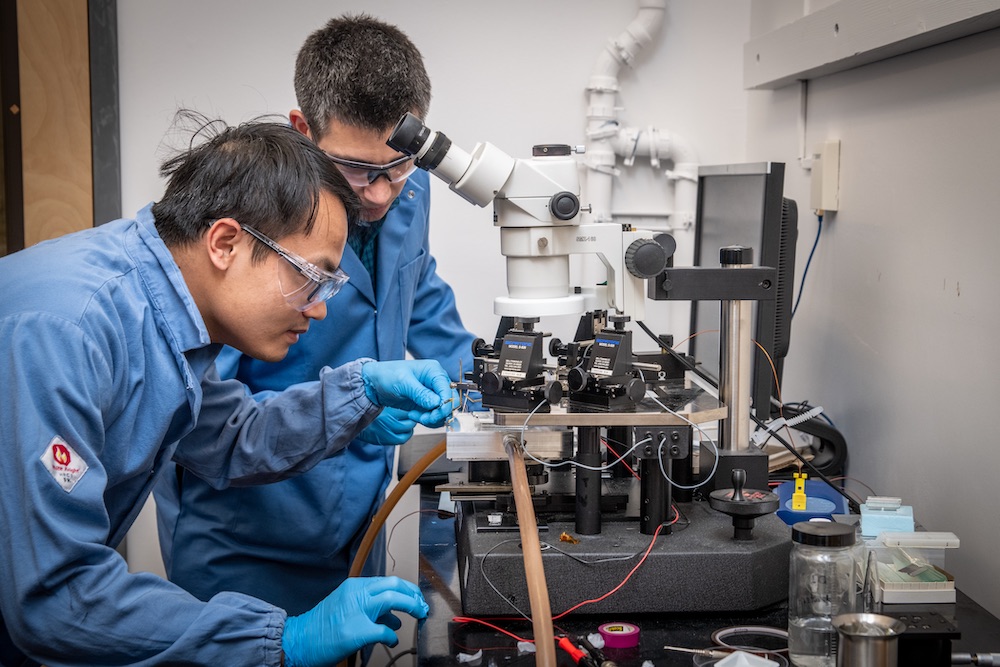

Based in the Bay Area of California, the three labs: Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Berkeley Lab), Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory are currently collaborating to support companies along the battery supply chain, offering their facilities for testing, modelling, optimisation and other aspects of R&D.

Today, China leads the way in energy storage manufacturing, from raw materials extraction and processing to designing and building components and complete systems. South Korea and Japan also have some market share.

Meanwhile Europe and the US, as late entrants to the game, are working to catch up but face an uphill and probably impossible task to overtake China. According to market intelligence firm Clean Energy Associates, more than 200GWh of annual ESS-specific battery production capacity will be added by Chinese manufacturers by 2025.

Nonetheless, both Europe and the US have begun establishing their own battery development and manufacturing hubs.

President Joe Biden and Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm’s Department of Energy (DOE) have explicitly stated their aim of fostering that US-based industry, describing it as a priority on several fronts, including decarbonisation, energy security, national industrial competitiveness and economic growth.

As regular readers of Energy-Storage.news will know, this has translated into billions of dollars being committed to the cause, including a US$335 million programme for battery recycling launched recently from funds unlocked by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The US’ other major recent climate legislation, included in the Inflation Reduction Act, offers manufacturers incentives for clean energy tech including batteries.

‘US is very good at innovation’

“It’s pretty clear that from the Department of Energy, and these investments, that one of the underpinning principles is to bring the battery manufacturing capability back to the United States,” Tony Van Buuren, deputy associate director for science and technology at LLNL said.

“[But] if you invest in technologies that are already going, [in other words] lithium-ion technologies that are primarily in Asia right now, that is no way to repatriate. What is the United States very good at? We’re very good at innovation.”

Van Buuren said that the way to repatriate the battery industry back into the US is to look toward what the next generation of batteries will be. From there, with guidance from the federal government and industry, a ‘game plan’ can be developed on how to progress and then manufacture that next gen tech – whatever that tech might be.

Noel Bakhtian, executive director at Berkeley Lab’s Energy Storage Center agrees, and says the key word should be “leapfrog”.

“We absolutely need to be creating those next gen [technologies] to leapfrog what’s going on. Thinking about the science of manufacturing, and how do we avoid having to spend decades on developing something from new material all the way to [commercialisation] because there’s always all of this mess in the middle, of figuring out how to manufacture at scale without constantly having to go back to the drawing board,” Bakhtian said.

In the full interview, to be published next week, SLAC’s Applied Energy Division director Steve Eglash said also that aiming for the next generation of storage technologies means something ideally suited to grid storage can be developed independently of the lithium supply chain, which is increasingly geared towards serving batteries on wheels – electric vehicles (EVs) – rather than stationary battery energy storage systems (BESS).

Not only could that reduce the US’ dependence on imported materials and products, but alternative technologies could be more sustainable too, Eglash said.

“Let’s think about materials that are Earth-abundant, that can be obtained in environmentally friendly ways, that are available, either in the US or from friendly countries, so we don’t end up overly dependent or dependent at all, on countries that we don’t have long, trusted partnerships with,” Eglash said.

The SLAC director referred to a need for full lifecycle or ‘cradle-to-grave-to-cradle’ analysis throughout the development and commercialisation of storage technologies.

“That includes things like embodied energy, recycling, reuse, all of those cradle-to-grave-to-cradle considerations, including the use of water. It’s a big, big deal.”