Earlier this month, John Goodenough, Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino were, of course, jointly awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize for Chemistry, as co-creators of the lithium-ion battery and therefore “a rechargeable world”.

The Nobel Foundation recognised not only the role of lightweight, portable battery technology for mobile phones, laptops and latterly electric vehicles, but also that it “can also store significant amounts of energy from solar and wind power, making possible a fossil fuel-free society”.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

“These energy-dense rechargeable batteries have revolutionised personal electronics, and transformed modern life around now-ubiquitous portable devices,” Kiwi Power’s head of optimisation, Thomas Jennings, says.

“Their ability to provide a repeatable, rapid response means batteries are now laying the foundations for renewable energy systems globally – providing vital resiliency and flexibility to enable wind and solar power to be integrated at scale. Simultaneously, through the electrification of transport, they offer the potential to finally wean humankind off its addiction to oil.”

Smarter batteries

Kiwi Power, a UK company with a background in operating megawatts of demand side response and latterly an aggregator of distributed energy, began operating Britain’s first grid-scale battery system in 2014.

“We now manage a 60MW portfolio of lithium-ion batteries on behalf of our clients,” Thomas Jennings says.

“In that time batteries have come to almost completely dominate UK frequency response markets, where a combination of speed and controllability make them an ideal asset.”

“The August blackout highlighted the importance of ultra-fast response to renewable electricity systems. The synthetic inertia batteries provide can slow the Rate of Change of Frequency and help to avoid generation disconnections which otherwise exacerbate the problem.”

Meanwhile, Moixa CEO Simon Daniel said that lithium batteries “have changed the world – and are essential for electric vehicles”.

“The UK alone will have billions of pounds of lithium batteries in the future EV fleet, able to deliver 10GW of smart energy storage for our nation’s wind and solar power, to keep the lights on and combat dangerous climate breakdown.”

What makes lithium batteries so special, Kiwi Power’s Thomas Jennings says, is that ability to control their use intelligently.

This also means, however, that they need to be carefully managed in terms of how often and how aggressively they can be cycled and the impact of use needs to be weighted against the revenue opportunity of each action.

“There’s more to managing batteries than simply charging and discharging in response to different grid or price signals. Batteries are built to deliver a certain number of cycles and there is a cost-benefit to every action,” Jennings says.

“Maximising value requires a detailed understanding of a system’s characteristics and means constantly evaluating the revenue opportunity against its impact on lifespan.”

In practise, this might mean that lithium-ion’s role is ultimately limited to short(er) duration storage for the most part, but Kiwi Power has seen analysis that says for the UK to meet 2050 carbon targets (net zero), for example, the country will need more than 100GW of new wind and solar, “balanced by 30GW of short duration storage”.

“For those that can compete and deliver, there is a huge market opportunity,” Jennings says.

Spirit of cooperation

Chemistry is one of the five annual Nobel Prizes given across different disciplines, each weighted to be of equal importance and selected for conferring the “greatest benefit” on humanity. Incidentally, however, the Nobel Foundation does point out on its website that in Alfred Nobel’s own life of course, chemistry was the most important of these five pillars.

Energy-storage.news would like to acknowledge the immense contribution the three scientists and their innovations have brought to our world and to our work. From a technology standpoint, lithium-ion batteries have indeed enabled renewable energy and distributed energy to go further onto the grid than ever before, as the commentary from Kiwi Power’s Thomas Jennings points out below.

We would also like to take a moment to hail the spirit of international cooperation that means three great scientists from three different continents were able to share their knowledge and build upon what each had achieved, for the benefit of all.

The three men discovered various breakthrough steps in stages. Whittingham, from Britain, during the 1970s OPEC oil price shock discovered whilst researching alternative energy sources that a titanium disulphide cathode in a lithium battery could intercalate (house) lithium ions.

“After Whittingham’s initial demonstration of a rechargeable battery based on lithium-ion intercalation into a titanium disulfide cathode with a metallic lithium anode, Goodenough improved the cathode to cobalt oxide,” Jennings says.

Whittingham’s invention, despite great potential and being energy-rich, remained “too explosive to be viable”, the Foundation notes.

Which is obviously never a good thing, but then US-born John Goodenough, some 20 years Whittingham’s senior, demonstrated in 1980 that cobalt oxide with intercalated lithium-ions could double the battery his predecessor had developed from two volts to producing up to four volts.

“The final step in creating consumer-ready batteries came in Yoshino’s replacement of the metallic lithium anode with one based on petroleum coke,” Jennings notes.

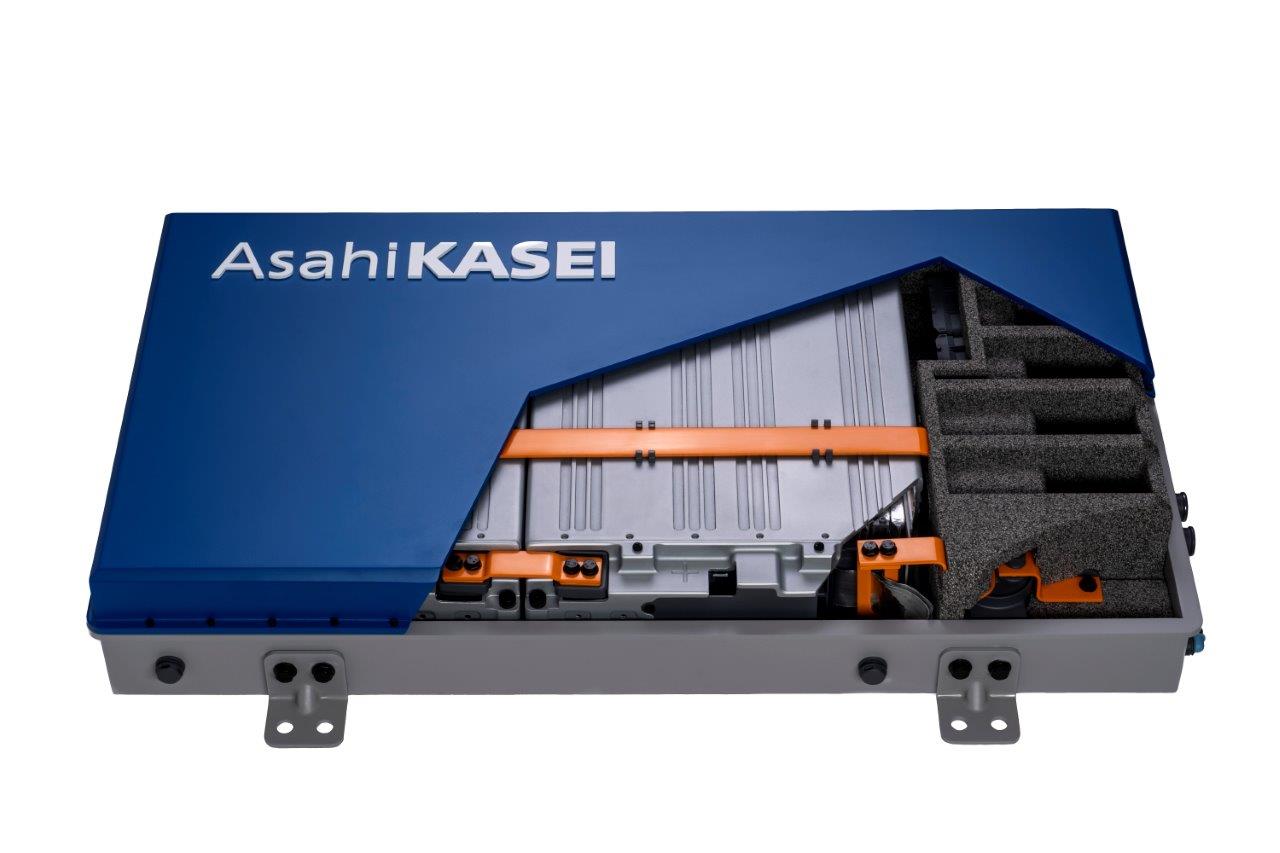

Japanese employee at technology company Asahi Kasei, Akira Yoshino, then created a rechargeable lithium battery in 1983, with his employer then filing a patent in Japan in 1985. The patent was then licensed to manufacturers including Sony, which commercialised the lithium-ion battery in 1991.

“My inventions have led to many patents for my company. The patents are not used to keep people out, rather we license our patents to encourage many other manufacturers to use our technology,” Yoshino said, following the announcement of the Nobel.

Hired to join Asahi Kasei in 1972, and one of the co-founders of the technology to enable the ‘Rechargeable World’, Yoshino said that he has since done further work to improve batteries for electric vehicles.

“These, I hope, will change the world again.”

“In his will, Nobel famously created the prizes to be awarded to those who confer ‘the greatest benefit on mankind’,” Kiwi Power’s Thomas Jennings says.

“It is hard to think of three more deserving recipients.”