The EU Batteries Regulation came into force in 2023, but its various stipulations become law over the next several years. What does it mean for Europe’s BESS developers, operators and suppliers?

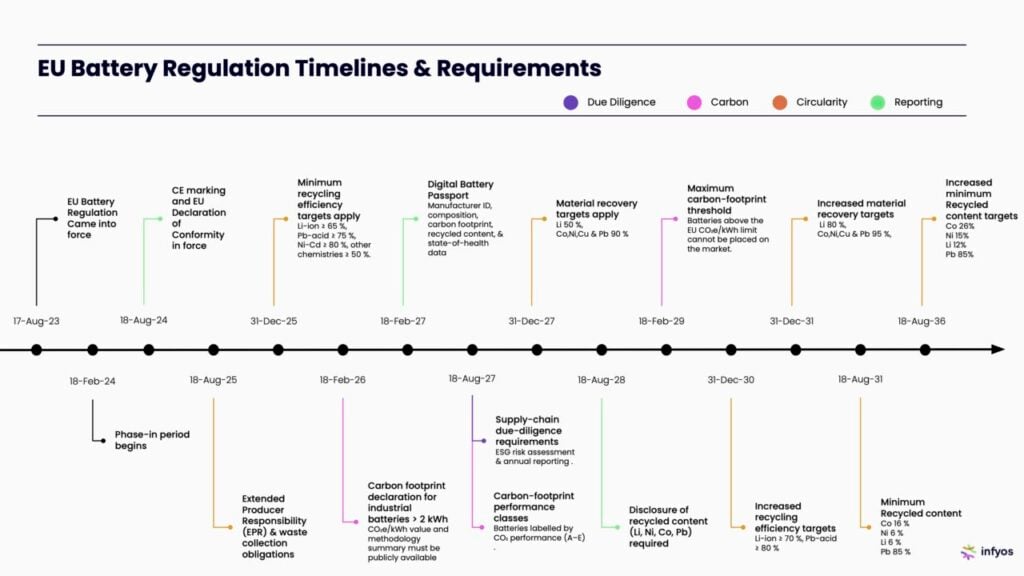

The package of measures aimed at increasing or maintaining the sustainability, circularity and quality of Europe’s battery ecosystem comes into force over 2024-2031. It includes due diligence and traceability reporting requirements, sustainable sourcing of raw materials, recycling and recycled content minimums, extended producer responsibility (EPR), and more.

“I think what is really interesting with this is its transparency element and the shift change in the way in which we need to approach this industry away from just a profit-driven one, to one where we focus on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) more broadly. And I think that for me is one of the most exciting things,” said Suriya Edwards, partner at law firm Freeths.

Edwards was in discussion with Energy-Storage.news Premium, along with Sarah Montgomery, co-founder and CEO of battery supply chain traceability platform Infyos, to discuss the Regulation’s requirements, what they mean for Europe’s battery energy storage system (BESS) industry, and what the separate market drivers are for more transparency and sustainability in the supply chain. Watch the full video of the discussion above or scroll down for our write-up.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

How ready is the industry, and how are developers affected?

We started out by discussing how ready the industry is for the swathe of requirements coming in.

“You find that even for the Tier-1 manufacturers, there is huge variance in how ready they are for the Regulation,” Montgomery said.

“The requirements are coming in at staggered intervals, this year we had EPR come in and in February 2026 we have product carbon footprints (for industrial batteries over 2kWh) coming in. From our research, less than half of the industry has verifiable data to prove they are compliant with the second, and that’s coming in in just three months time.”

The firm has provided a useful infographic giving an overview of what aspect of the Regulation comes in when, shown below, including the Battery Passport.

The Regulation applies primarily to the seller, i.e. the company putting the battery product into the market. So, in most cases, that would be a lithium-ion manufacturer; however, in the case of BESS, it could be the system integrator that has assembled a BESS, which it then sells into Europe. However, it still matters to developers and BESS operators buying the equipment.

“The BESS developers aren’t necessarily under the regulation, but there could be huge consequences for them of not having the right processes in place to ensure they are working with a supplier that doesn’t meet the regulation. That could mean blocked products, supply chain delays and project overruns,” Montgomery said.

“Some BESS OEMs have detailed information on their website, and others can be lacking on publicly available forums. Discussions in respect of ESG, particularly in respect of the detail can be subject of confidentiality provisions / NDAs as they speak to product price points,” Edwards added.

Both agreed that even with the regulations in place, the financing community will be the big ones driving enforcement among BESS buyers and suppliers.

Supply chain due diligence requirements

These requirements were initially set to come in 2026 but were pushed to August 2027 because the industry and oversight bodies would not have been ready in time.

“Traceability, which is one of the requirements, will be exceptionally complex for people to comply with. While Europe wants to push the industry to be as safe and sustainable as possible, it has had to balance that with what’s practically feasible in the industry and the need to not slow down the deployment of batteries and BESS for net zero,” Montgomery explained of the delay.

Edwards said the regulation has fundamentally shifted commercial discussions in BESS supply, creating extremely candid discussions on all things ESG. It has also moved these considerations from something of a tick-box exercise at the procurement stage to something that needs to be applied across the whole lifecycle of projects.

“This is repeat factory visits, this is changes you need to report on over time, and that will be challenging for OEMs entering the market, to have that 10, 15, 20-year view on how they will be reporting on these things, both from a global political point of view but also from pricing,” Edwards said.

“Right now, OEMs publishing traceability statistics and information needs pressure from an external stakeholder, usually a financing party, but I think it will start to become the norm.”

“And this ESG side coming in to things and influencing where you buy your products, and how you are doing, will naturally influence price. That tension that exists between the commercial aspects and the regulatory aspects is something which I’m seeing more and more play out in the contractual side.”

EPR

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) is the obligation for producers to have in place a solution for the collection, treatment and recycling of end-of-life (EOL) batteries. This came into force in August this year, after which Edwards and her colleague Deborah Harvey co-authored a guest blog on it for Energy-Storage.news.

“In the EU context there is the possibility of tying into your contract price the aspects of collection, treatment and recycling, while some are just adopting an open book accounting mechanism to deal with it a future date,” Edwards said, adding that others might be hoping that a bespoke commercial agreement complies with EPR, though whether it will is not clear.

The EPR change in August also marks a divergence between the UK and the EU, which Edwards discussed more in August’s guest blog.

What are the penalties for non-compliance?

Importantly, while the Regulation is EU-wide, enforcement is down to individual member states, Edwards explained. And penalties for non-compliance also tend to be less heavy-handed than in the US, Montgomery added.

Though both said they expect the big suppliers will not risk non-compliance and the reputational, as well as commercial, risk that would entail.

Edwards: “You will have to look at how a contract plays out in the German market as opposed to the Italian market because there are a lot of local civil code variations. The way one court approaches things is different from country to country. So it’s it’s not a one-size-fits-all answer for from an enforcement perspective and it’s really important that anyone listening who’s concerned seeks local jurisdictional advice.”

On the actual measures, Montgomery added: “The US spends around US$100 million a year on enforcing the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (ULFPA), for example. Shipments get blocked there. Europe on the other hand does not have that same budgetary allocation for enforcement. So generally speaking enforcement tends to be more about voiding contracts and warranties if they are not compliant, though that’s a big business risk.”

“We’ve also seen in the automotive space that, rather than stuff being blocked at ports, you see civil lawsuits where, say, an NGO or group of legal activists takes a company to court based on them not complying with the law.”

The tension between the politics of climate change and the politics of the Regulation

“The other thing worth mentioning is the politics of Europe, when we talk about enforcement. There’s something like €800 billion of investment going into the European grid by 2050. Energy storage will be critical to it,” Edwards pointed out.

“So if you have a member state taking issue with a battery OEM supplying mega kit at a time when we have to transition, there is going to be a tension between delivery of this massive infrastructure change and the politics of the contract, recycling, and all the good stuff we’ve been talking about,” Edwards pointed out.”

Similarly, it is likely that when the Regulation was first drafted, the forecasts for Europe’s domestic homegrown battery manufacturing industry were much more bullish than the reality that has been borne out.

“There was a dream that maybe by putting in a sustainability safety regulation in Europe where we’re known for loving, sustainability and safety, that it would mean an encouragement of a local European market off the back of that. What’s actually happened is the Chinese manufacturers have got their heads around it and are some of the best prepared out there,” Montgomery added.