Matt Szwec, an energy trading analyst at Fluence, discusses virtual battery toll agreements and how they operate in Australia.

Australia’s energy storage boom is accelerating, with +200MW, +4-hour battery energy storage systems (BESS) becoming the new normal in Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM). But building assets of this scale demands serious capital – and banks typically want a high degree of revenue certainty before lending.

In an energy-only wholesale electricity market like the NEM, revenue certainty is difficult to achieve without the assistance of financial contracts.

Government-backed contracts like the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) are playing an important role in supporting projects to reach financial close, but demand for BESS projects is outpacing the supply of available support, and a CIS contract alone may not provide sufficient revenue certainty to achieve financial close.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

To close this revenue certainty gap, developers are turning to bespoke offtake agreements. The original offtake model was the physical battery toll, which is effectively a lease arrangement where an offtaker pays a fixed fee in exchange for full operational control overtrading of the BESS and the market revenue it generates—the owner hands the “keys” over to the offtaker for a period of time. These deals have historically run 5–10 years, after which control reverts to the owner.

Today, other contracting models are becoming increasingly popular, such as virtual battery tolls and capacity swaps, driven by accounting, regulatory, and operational considerations. Like a physical battery toll, these contracts aim to deliver revenue certainty, but they function very differently.

What is a virtual battery toll?

A virtual battery toll is a commercial carve-out within a physical battery – like having dispatch rights to a “battery within a battery.”:

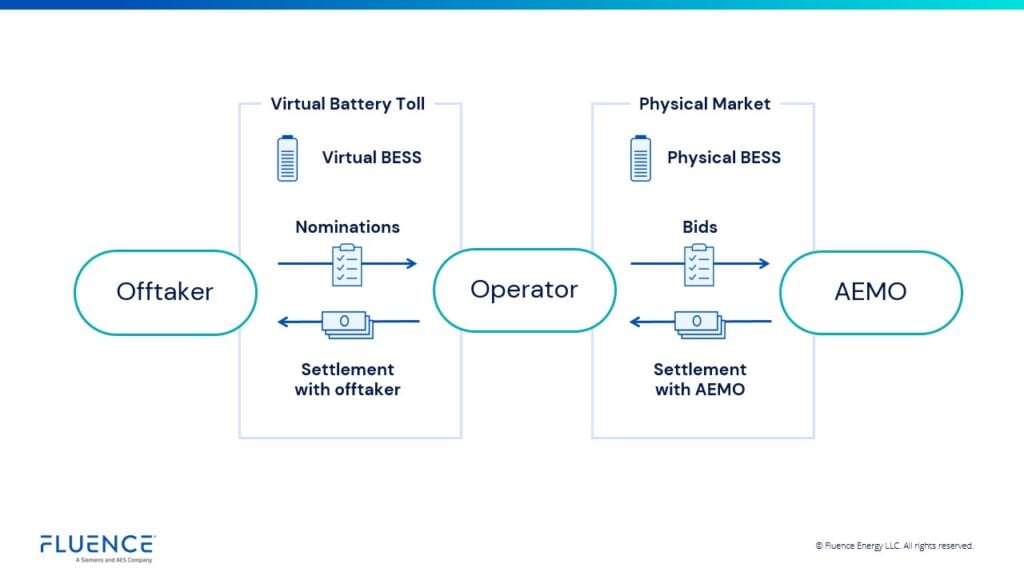

- The BESS operator – the registered Market Participant with the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), responsible for bidding and settlements. This party is typically – but not strictly – the BESS’ owner.

- The virtual offtaker – a third-party seeking exposure to battery trading without owning the asset.

The offtaker gains access to a “virtual battery” which they can instruct to charge or discharge, and the dispatch of the virtual battery is settled with the operator, at spot market prices. This allows the offtaker to trade virtual energy at spot price and capture the upside of market volatility.

Meanwhile, the operator receives a fixed recurring payment from the offtaker, supporting project finance and, importantly, retains physical control of the BESS and all its market revenues. There is a settlement between AEMO and the operator for the dispatch of the physical BESS, and another between the operator and offtaker for the dispatch of the virtual battery.

Virtual battery tolls are typically structured around trading BESS for energy market revenues only and exclude ancillary services.

Why do virtual battery tolls exist?

Banks need predictable cashflows to underwrite debt. For BESS operators, annual revenue relies on a combination of steady daily performance and the occurrence and capture of infrequent but impactful high prices. These are closely tied to events in the market or on the power system which can be difficult to forecast with precision.

This uncertainty can make it challenging to convince some lenders who are less familiar with the dynamics of the NEM of a BESS project’s bankability. Virtual battery tolls offer a solution: they provide a stable, contracted income stream that helps developers demonstrate revenue certainty and secure financing.

Unlike physical tolls, virtual battery tolls can be sold for just a portion of the physical BESS. For example, an operator might contract 50% of the capacity of the BESS to an offtaker and retain the rest to trade as merchant, balancing a fixed revenue stream with market exposure.

For offtakers, virtual battery tolls offer access to battery trading upside without the cost, compliance overhead, or capital requirements of developing, owning, and operating a physical asset. Because they’re financial instruments, virtual battery tolls are not treated as a lease and therefore don’t have an impact on the balance sheet like a physical toll would.

Virtual battery tolls can lower the barrier to entry to trade energy, and are appealing from an accounting perspective, so they can attract a broader range of participants beyond traditional energy companies.

How do virtual battery tolls work?

Virtual battery tolls operate in a “shadow energy market.” The BESS operator acts as the market, and the offtaker acts as the participant. Offtakers send virtual instructions or “nominations” to the operator to charge or discharge the virtual battery.

Settlement calculations are based on the dispatch of the virtual battery and resolved at real spot market prices. For the case where spot prices are positive:

- The operator pays the offtaker for discharging the virtual battery.

- The offtaker pays the operator for charging the virtual battery.

The opposite holds true where spot prices are negative.

Practically, the virtual battery parties typically settle net revenues at month’s end. Settlements for the virtual battery are typically in favour of the offtaker, similar to how AEMO net settlements for the physical BESS are typically in favour of the operator.

The nominations that an offtaker sends are subject to an agreed gate-closure time, validation rules, and must respect an agreed virtual battery framework, which tracks virtual energy throughput, virtual cycles, and virtual state of energy. The virtual battery must be “charged” with a sufficient virtual state of energy before it can be “discharged,” ensuring equivalent behaviour to a physical BESS.

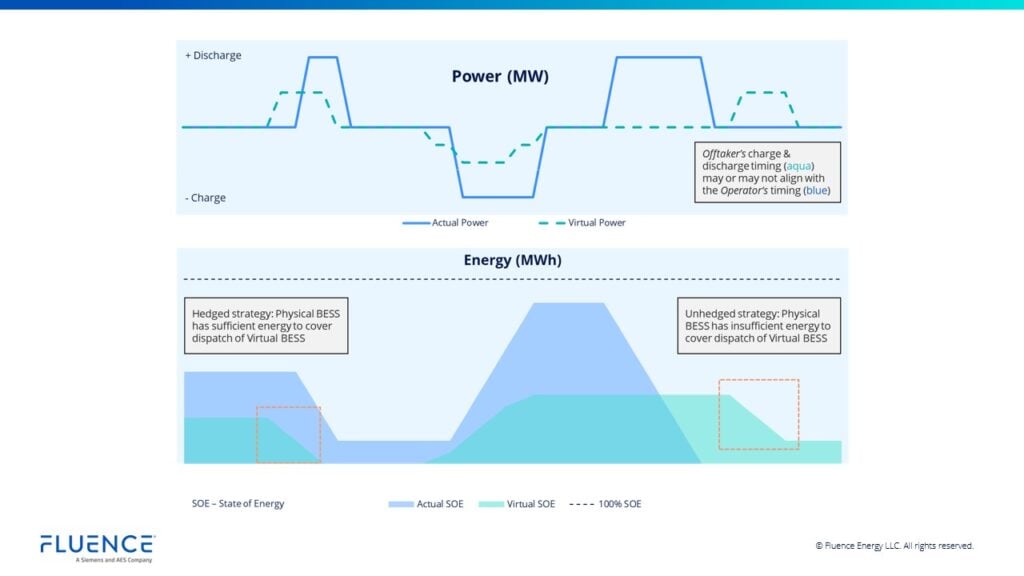

Where this gets interesting is that the operator is not obligated to follow nominations with the physical BESS to deliver energy into the market. Whether the operator decides to follow the nominations or not, will impact the contract risk they are exposed to, the upside they can capture, and can ultimately impact the bottom line.

Strategic dispatch: to hedge, or to optimise?

Operators have two choices:

- Follow the offtaker’s nominations: dispatch the physical BESS at (at least) the same volume as the virtual nominations. The energy settlement from AEMO acts as a back-to-back hedge with the settlement to the offtaker, which often still generates additional revenue through ancillary services. This reduces contract risk, as both settlements align on spot price, but may come with the opportunity cost of foregone upside.

- Optimise freely: dispatch the physical BESS to maximise revenue from both the contracted and merchant portion of the BESS, aiming to outperform the virtual battery toll by co-optimising Energy and FCAS or taking calculated trading risks.

The second choice offers greater potential upside but introduces greater risk. It’s a strategic call: hedge nominations for certainty, or trade for potential gains.

Offtakers will also vary in their objectives and nomination strategies. Some may aim to optimise merchant revenue and mimic the behaviour of a merchant BESS in their nominations, while others—like retailers—may use virtual battery tolls to optimise a broader portfolio, including load positions or other assets, producing a different set of behaviours.

For the operator, virtual battery tolls lie at the intersection of the physical asset, the energy spot market and commercial contracts, so knowledge of all three is important to manage risk.

Optimising the net revenue from the merchant and contracted portion of the BESS can be complex and involves managing a “battery within a battery,” so any operator will need to have a capable bidding system to help them manage the communication of nominations from their offtaker, their risk management decision-making, and their transmission of market bids to AEMO.

As virtual battery tolls become more common, we expect they will potentially change how BESS are traded in the market by creating an incentive that pulls BESS away from the traditional buy-low-sell-high merchant behaviour.

They will support a diversity of players with diverse objectives on the virtual layer, which may be reflected on the physical layer depending on how the operator chooses to respond (hedge vs optimise freely), leading to a diverse set of behaviours in the physical market.

Virtual battery tolls are quietly transforming the economics of energy storage in Australia. By blending financial innovation with market exposure, they unlock capital, attract new market participants, and support the rapid deployment of BESS – without sacrificing operator control or triggering lease accounting burdens.

These structures reflect a deeper shift: the move toward modular, market-integrated contracting for BESS. As the market evolves, virtual tolls may not be the only model, but they signal a maturing approach to risk-sharing, asset monetisation, and market access.

About the Author

Matt Szwec is an energy trading analyst in Fluence’s Digital team. Matt works closely with Fluence’s Market Participant customers to help them build and operationalise their trading strategies using Fluence’s Mosaic bidding software. Matt led the development of Virtual Battery Tolling capabilities within the Mosaic software.

Prior to Fluence, Matt was part of the core team at Banpu Energy Australia, involved in developing a data and analytics platform, and the technical asset management of utility-scale solar farms.