The award of contracts to battery storage developers in a recent auction by Italy’s transmission system operator proves the technology’s competitiveness in providing grid services once again, an analyst has said.

Terna, which manages the Italian electricity grid, awarded just under 250MW of contracts to provide the Fast Reserve service to the grid a few days ago. It assigned three tranches of contracts, in the Central and Northern regions, in the Centre-South and on the island of Sardinia. The systems are expected to be online by 2023, having won five-year contracts to the end of 2027.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

A range of stakeholders won out, led by utilities ENGIE and Enel's innovation and new technologies arm Enel X, which got 70MW and 65MW of the contracts respectively. Other winners included EPC company METKA EGN, solar company Trina Solar and Italian oil and gas company Eni. Contracts were awarded at an average weighted price of €29,500 (US$35,870) / MW / year.

Corentin Baschet, head of analysis at energy storage consultancy Clean Horizon told Energy-Storage.news that most market regulators in Europe are “in the process of opening their different ancillary services to batteries: this auction proves again that batteries are very competitive to provide a fast symmetric frequency regulation service”.

“Frequency regulation services are the easiest starting point to deploy batteries in a given country,” Baschet said.

“I don’t know of many countries in which batteries would not be cheaper to provide these services than conventional power plants which are missing out on wholesale revenues while reserving capacity for the frequency response products.”

Fast Reserve is a bi-directional ancillary service that helps to maintain the operating frequency of the grid within boundaries that prevent it from experiencing failures through the imbalance of supply and demand of electricity. As the name implies, assets participating in this service have to do so quickly, within 1 second of receiving a signal from the grid that an error needs correcting.

Similar market opportunities have opened up in various territories in recent years, and Baschet said “this is not much different” than Enhanced Frequency response (EFR) in Britain, Frequency Control Reserve (FCR) in France and Germany or the Fast Frequency Response (FFR) service in Ireland’s DS3 grid services market.

“I’m convinced batteries will be successful at providing this service,” Baschet said.

“Changing the grid operation to enable small distributed assets like batteries to support the grid requires a lot of adaptations for a national system operator but this is moving in the right direction.”

Fast Reserve will be among the available opportunities opening up on the grid

The analyst said he expects most of the projects involved to be new-build battery storage assets, although the fact that ENGIE’s energy storage subsidiary ENGIE EPS has said it will deliver 25MW of its Fast Reserve availability from a vehicle-to-grid (V2G) project in Turin implies that “some utilities have implemented some innovation” too, the Clean Horizon analyst said.

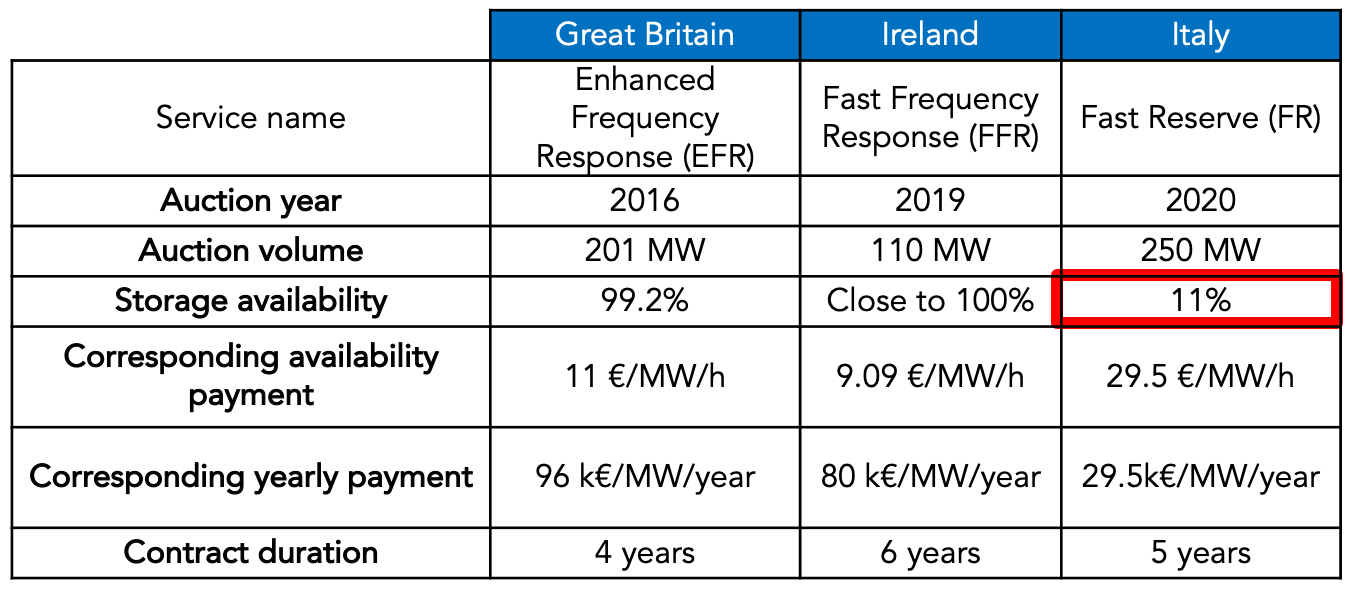

Where Terna’s Fast Reserve opportunity really differs from some of those others mentioned however, is that it only requires 1,000 hours of activation per year from participating battery systems. In Great Britain and Ireland, as shown in the chart the analyst provided, Baschet pointed out that storage assets must be available for 99.2% and close to 100% of the time to fulfil the terms of those countries’ EFR and FFR contracts respectively.

“Terna is in the process of opening new revenue streams to storage such as primary reserve, secondary reserve and the MSD market (equivalent to the UK’s Balancing Mechanism which matches supply and demand in real-time on the grid).”

Batteries that have won Terna contracts, therefore, will be available to yield other revenues from those forthcoming streams, as well as performing wholesale market arbitrage, for close to 90% of the hours in a year for the five-year terms of their Fast Reserve contracts.

“Developers and utilities are betting these revenue streams will be opened to batteries by the time they develop their assets,” Baschet said.

“Otherwise arbitrage on [the] wholesale market already captures some revenues, even though this is expected to be low in continental Italy.”

Pricing structure rewards the risks that battery players will be taking

The prices given for contracts were much lower than had been anticipated by some: around €23,500 / MW / year for 118.2MW in Central and Northern Italy, around €27,300 / MW / year for 101.7MW of contracts in the Centre-South region, and a weighted average price of €61,000 / MW / year for 30MW of contracts in Sardinia.

The prices of contracts in Sardinia are much higher due to it being an island territory with “a more challenging access to the network” and the highest regional electricity prices in Italy.

However, Baschet said, when the low required availability of storage in Terna’s auction is taken into account in comparison to markets in other countries, the prices are actually “more than three times as much” that is paid in those other markets for comparable services.

“The average yearly prices are much lower than prices for similar frequency response services contracts in other countries such as Great Britain and Ireland: battery prices have reduced but developers will still need to find €40,000 to €60,000 / MW / year on other markets: which they should be able to find during the remaining 89% of the time,” Baschet said.

“Actually if you value the contract per hour of fast reserve provided you end up finding that each hour of availability will be paid by Terna €29.5 / MW / hour: which is more than three times as much as what is paid in other countries – in France and Germany, current average FCR price is €10 / MW / hour.

“However this high availability price reflects the risk that developers are taking while betting on the revenue streams that they will be able to access in 2023: today only arbitrage is really accessible. Of course utilities such as ENEL and ENGIE will have more possibilities to value these flexible assets within their thermal or renewable portfolio.”