The COVID-19 crisis is bringing into the public eye the US’ dependency on importing goods, particularly batteries for advanced energy storage and electric vehicles, the CEO of a battery materials startup has said.

Dr Francis Wang, head of Nanograf, a US company working to commercialise a high energy density battery anode made with a composite of silicon and ‘curved’ graphene, replacing existing anodes which use graphite, said that the situation created by the novel coronavirus “is bringing to light… cracks in US infrastructure and the supply chain”.

Enjoy 12 months of exclusive analysis

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Annual digital subscription to the PV Tech Power journal

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Asked by Energy-Storage.news for an upstream technologist’s opinion on how supply chains have been impacted by the shutdown of operations in factories first in China and then elsewhere in the world, Wang said that “the US doesn't make anything anymore, and we are having trouble because we don't make equipment or materials and batteries is one of them”.

“Most battery production is split between Japan, Korea and China. It used to be roughly one-third, one-third, one-third, in terms of output. But in recent years it’s become closer to 60-70% of lithium ion batteries being made in China. That’s a big deal,” the Nanograf CEO said.

“Energy storage, especially portable power, for electric vehicles or iphones, iwatches, consumer electronics, and other use cases — it’s all linked to China. Coupled with the trade war – and the increased tensions generally between the US and China – you wonder whether the US might be in trouble because China isn’t very happy with us right now.”

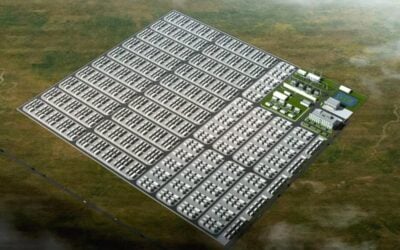

All the US has these days in terms of advanced battery technology production, is the Nevada Gigafactory operated by Tesla-Panasonic, Wang pointed out, with legacy battery companies like Duracell and Rayovac largely reliant on alkaline tech: “a relatively antiquated technology”.

An intercontinental ‘gigabattle’

Nanograf CEO Wang pointed out that the US government has recently said it will put a lot more money into production of batteries domestically, not least because national defense products like drones rely on battery power. The Department of Energy has launched a US$158 million “Energy Storage Grand Challenge”, which will seek to foster domestic supply chains. As well as increasing the “development, commercialisation and utilisation” of energy storage technologies, the US wants to lower its reliance on imported raw materials including cobalt and lithium.

Similarly, in a recent interview with Energy-Storage.news, Emad Zand, energy solutions head at European battery manufacturing startup Northvolt, said that the idea of a European continent unable to compete with China on making its own battery devices is “a scary thought”. Northvolt is planning European facilities to rival Tesla’s Gigafactory in size, while Tesla also has its own ‘GigaBerlin’ under development. Others are also springing up, including a recent loan of close to half a billion dollars to South Korea-headquartered battery maker LG Chem from the European Investment Bank.

“The largest future consumer of electric batteries is the largest producer as well, and that’s China. They will have a lot of supply needs to cater for before there’s the need to export that. In the shorter timeframe, there is a chronic undersupply, which also then puts European companies at a disadvantage,” Northvolt’s Emad Zand said, applauding what he described as the foresight of European Commission strategists such as Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič in planning to create a battery manufacturing ecosystem for Europe.

In 2018 as EC vice president for energy, Šefčovič had argued for the need to set up sustainable, green battery manufacturing at scale in the continent. Northvolt claims that using mostly wind and hydro power at its production facilities in Sweden, it will be able to reduce the carbon footprint of battery manufacture by “approximately 69kg of CO2 per kilowatt-hour of battery that you deploy,” Zand said, which could be as much as 71% decrease in CO2 footprint over competitors' products.

“If you don’t have the internal market set up, the internal supply, you will be the last to electrify. And that is a very scary thought, because this is a race of technology and if Europe does not win a race of technology the whole future industry might slip out of its hands.”